Enter a capRecruitment information for This Sickle Cell Life participants (Photo: Anne Koerber)

New month, new writing. I’m taking this opportunity to take my mind off COVID-19 – there’s certainly plenty of valuable coronavirus articles you can find elsewhere – but that’s not to say what I’m posting today doesn’t cover some really important work.

I thought I’d write about the work we’ve been doing at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine on This Sickle Cell Life, a recently completed qualitative research project that talks to young people about their lives and experiences of having sickle cell disease. The project is particularly special, I think, because it also works directly with sickle cell patient experts and a sickle cell carer to produce some of the most exciting research I’ve ever done – but more on that later. I should also add that some of what I’m writing about are based on team discussions and reflections; we’re writing this up in more detail with our co-authors and I’ll keep you posted on how it progresses.

I got involved in This Sickle Cell Life with Professor Cicely Marston and Dr Alicia Renedo when I started here at LSHTM in 2017. Funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), the project explores how young people experience transitions in moving from paediatric to adult healthcare services. This includes for example how our participants experience GP surgeries, scheduled hospital visits or unscheduled (i.e. emergency) trips to A&E. We also explored the personal and day-to-day experiences of young people living with sickle cell disease. We were aiming to answer questions including: What is the relationship between a young person with sickle cell and their doctor, and how does this change if you move away from home for college, university or work? And why do young people with sickle cell delay going to the emergency department when they have a sickle cell pain crisis? (Read this excellent overview by Sickle Cell Society for more on pain). We then cast the net wider to think about family, school, sex and relationships.

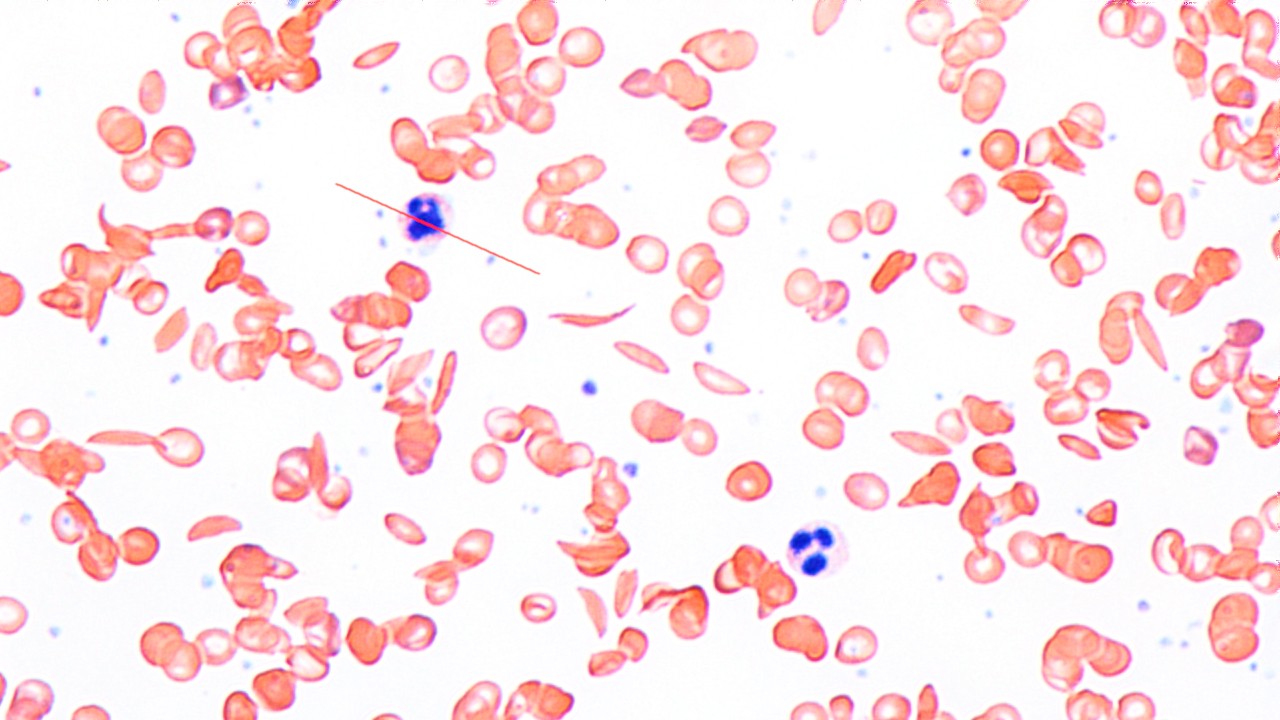

Our aim was to offer a much-needed sociological picture of how a young person with sickle cell navigates their life and their future, to mirror the more extensive clinical and quantitative research that has been published about the condition. That’s not to say that sickle cell research is exactly a crowded market – Simon Dyson, who has made brilliant sociological contributions over many years, has rightly noted the lack of sickle cell research compared to other chronic health conditions, and how social, economic and ethnic determinants play into this marginalisation:

‘…impairment is primarily socially created by environmental factors, consumption patterns and accidents and not by genetic disorders.’ (Dyson 1998: p.123).

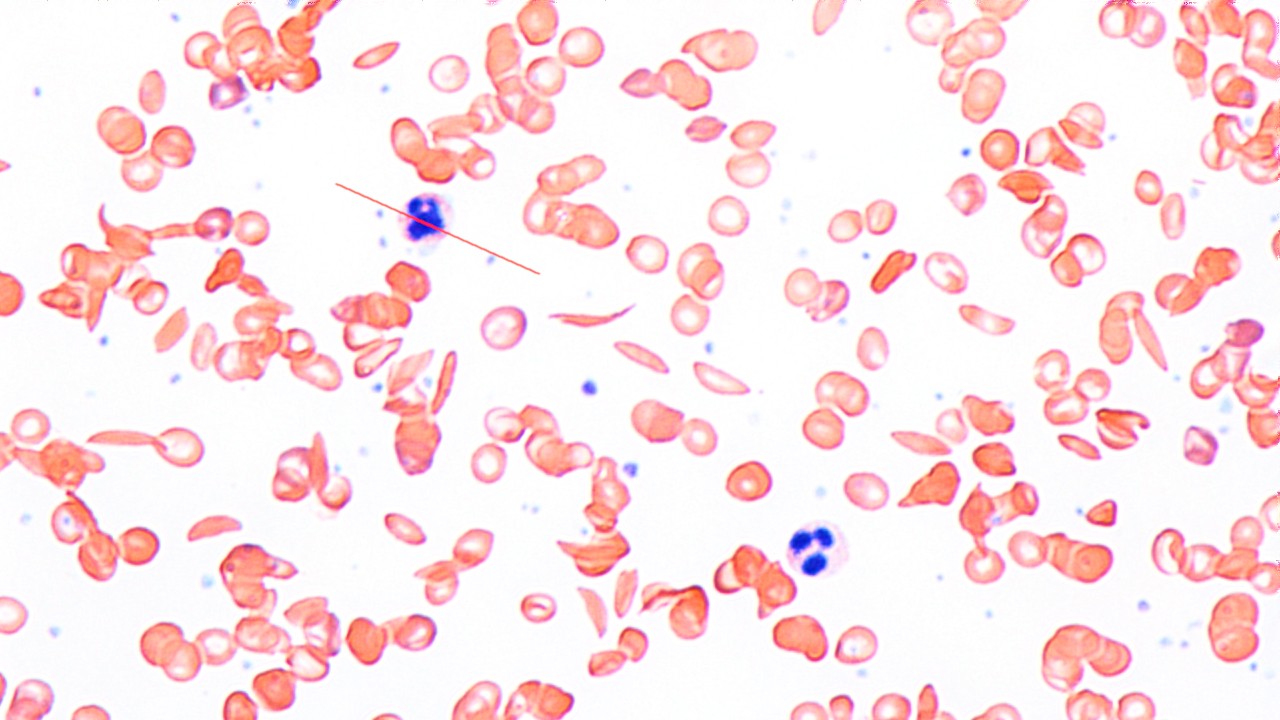

Sickled cells (Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

Co-production

Fieldwork was already expertly wrapped up by Alicia when I joined the project, but I got to be part of the really interesting results analysis, discussion and dissemination work, including an engagement event with the public which in turn led to some fantastic community projects of its own. You can read more about the work here, but what I’m going to focus on in this blog was the role of ‘co-production’ in the project: put simply, that means working with different ‘kinds’ of people to produce research that is a collaborative effort. Co-produced research recognises that expertise is held by a range of people rather than only the usual suspects (in this scenario, academics or clinicians). Advocates of co-production hope that the research findings developed are more rounded-out and take into account the ‘embodied’ knowledge of people who are living the journey themselves (see Renedo et al., 2018 for more).

One of the distinctive features of This Sickle Cell Life was that it was co-produced with two young sickle cell patient experts and a sickle cell parent/carer expert from the outset. All three have extensive knowledge of sickle cell and life with sickle cell, and already advocate for healthcare improvement in their own lives. They were involved long before I was – right from the project planning and application stage before funding was granted, in fact. They were also paid for their time. Partnering with these three experts added a very important facet to the research we conducted. There is a lot of talk in public health research about ‘PPI’, or patient & public involvement with healthcare, similar in some ways to P.A.R (participatory action research) in social sciences, particularly geography. In the NHS, the motto ‘nothing about me, without me’ represents one way in which patient involvement is rationalised. Funders and grant-giving bodies are (rightly) keen to see meaningful involvement with the communities (sometimes also called beneficiaries) who are most relevant to the research being done. Co-production can also shine a light on the power imbalances than often happen in a traditional researcher-participant relationship in social sciences research which can reinforce all sorts of unhelpful hierarchies and prejudices.

Documenting the participatory dissemination event for This Sickle Cell Life (Photo: Anne Koerber)

In our project, we agreed with our patient experts that it was particularly important that their voices were heard, because they contributed expert knowledge of their bodies and their own health conditions, as well as helping us at the findings stage highlighting themes that were most pertinent to improving healthcare environments for people with sickle cell. We further argued at every stage (to colleagues, institutions, sceptics – anyone who would listen basically) that our involvement processes needed to be considered, balanced, and properly thought-through – lip-service involvement doesn’t help any party and it is not in the spirit of meaningful participation. We wanted to amplify less-heard voices and hear stories from our patient experts and carer experts because their analysis of their own, and others’, experiences of sickle were invaluable. Our collaborators’ input contributed a different side to more traditional qualitative research; as a team, we worked to interpret the data and draw out the implications for practice.

The highlight of the project for me was not just the valuable findings that came out of 80 interviews with young people, which are research outputs of their own brilliantly managed by Alicia (which you can read for free here), but the process of co-producing research with patient experts and carers. I have discussed the idea of co-production a bit in my own digital technology and sexuality research, in which I (loosely) explored the co-production by both researcher and participant of a safe discursive space for covering sensitive topics in sex and sexuality in fieldwork research (which you can read for free here). But This Sickle Cell Life made co-production central from the start and throughout the full four years of the project; it is clear to me only now how truly different this way of working is, and the value it adds.

Attendees at the participatory dissemination event for This Sickle Cell Life (Photo: Anne Koerber)

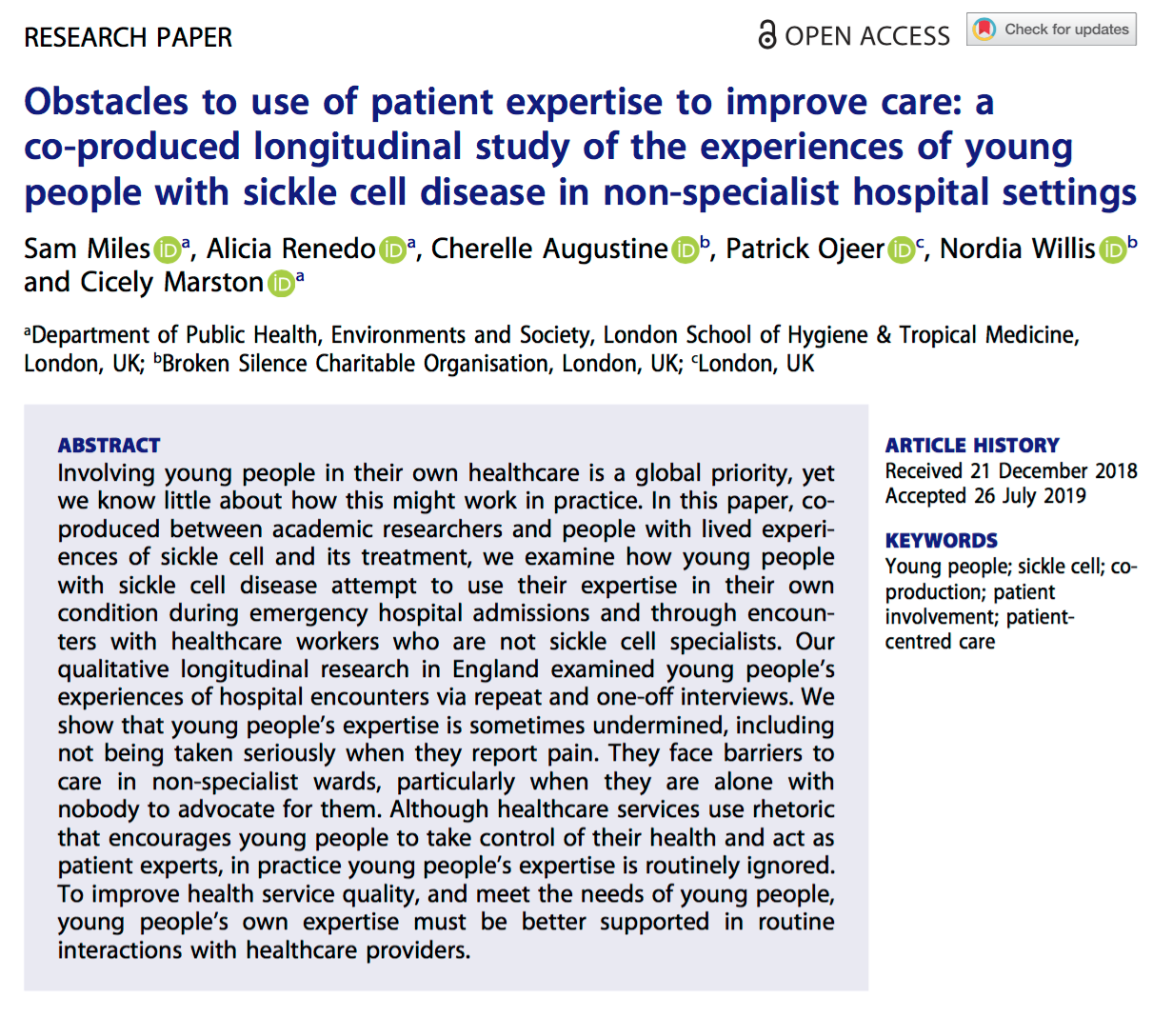

The winding road to publication: How expertise is framed in academia

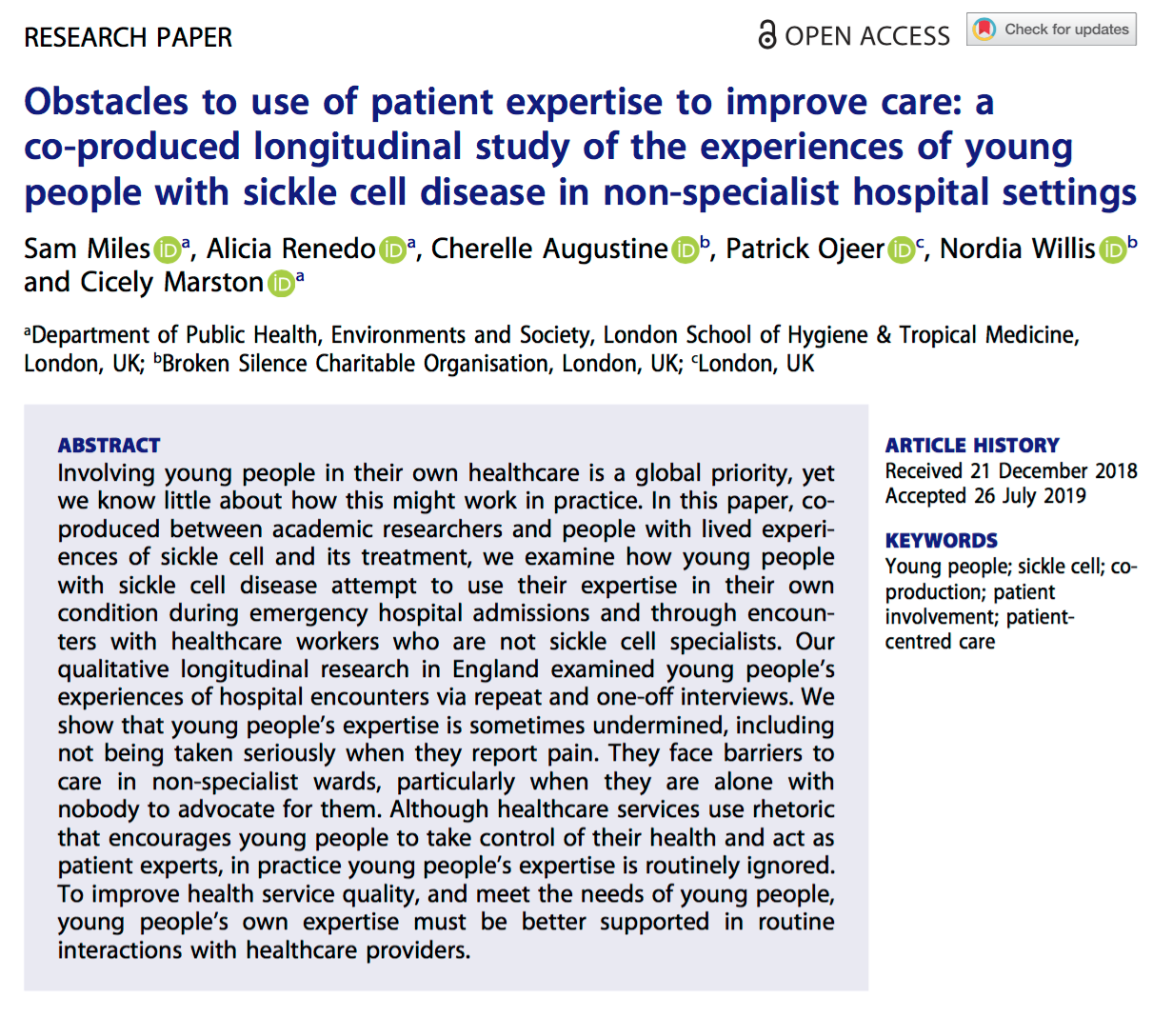

What was interesting was how our co-produced research outputs were received by peer reviewers for academic journals. Having learnt so much from our patient experts about how their experiences reflected what our results showed us about participants’ experiences, we invited them to write an academic article with us. We did this by discussing study findings with them and inviting them to discuss these themes with us as I took notes and recordings to write into a larger discussion. It was a long process, involving lots of conversations in cafes, on the phone and by email to coordinate our different experiences and expertise. Academic articles are a very specific product, and only 7 years into academia I’d largely forgotten how alienating the process can be for the uninitiated. I think it says a lot about the publication process that it really does resemble an iniation of sorts: even within its confines, privileges exist and some are more able than others to call on resources, connections and knowledges to participate in system).

However upon submission, several reviewers critiqued what they felt to be overly personal accounts of sickle cell. Even having noted our co-produced efforts and celebrated this ethos, reviewers still picked out patient expert passages that they felt were lacking objective research – questioning the expertise of those who were best placed to be reflecting on the study findings. Where our patient experts told us how their experiences chimed with those of the participants when it came to hospital care or chronic ill health or family issues, and I wove these reflections into our discussion section, reviewers felt this expertise was anecdotal or somehow unscientific – as if the rest of the qualitative dataset was by contrast unobjectionable or markedly positivist when of course it wasn’t. We were in the paradoxical position of amplifying the expert knowledge of people with sickle cell and yet that knowledge was somehow too ‘real-life’.

We were in the paradoxical position of amplifying the expert knowledge of people with sickle cell and yet that knowledge was somehow too ‘real-life’.

I have sympathy for the reviewers, too, because despite the best will of a whole range of actors to more actively incorporate a range of knowledges into academic publications, establishment traditions prevail. This clashes with what I guess I would call the out-of-place-ness of equitable authorship, which synthesises a range of voices, including those which are non-establishment and may contribute in different (often refreshingly different) ways than are standard. None of this is to say that it wasn’t a valuable experience, but it was a long one. Critical Public Health and its editors did support our approach, with suggestions back and forth, and published what will be the first of several co-produced articles (read it for free here).

That leads us to one of the curious tensions in this kind of work – our collaborators are clearly experts, but they’re not academics. Does that matter? Well, it shouldn’t – especially given the UK NHS drive to centre patients and public at the forefront of research and healthcare involvement. And yet the process of publishing papers with our patient experts was not straightforward. It required different ways of working than what we were all used to, and different approaches – and that’s before we consider the lengthy journey we then had publishing our co-produced academic article, where roadblocks re-emerged.

I came to see that the key contribution of any author is their contribution to ‘the work’, and this can go far beyond typing up results or making an argument for changing UK healthcare practices in an academic article. Instead, it is about having conversations – in ways that ensure equity between all parties – and then using academics’ toolkits to package this co-produced knowledge whilst maintaining its integrity. For us, a more liberatory outcome would have been yet more unconventional than the finished piece. Maybe this would have taken us further from what makes an academic article an academic article. Well, you might argue, if you really want to publish more collaboratively, perhaps a different format would be better suited – a commentary, or an editorial, or a blog – and we are in the process of doing all those things. But this argument overlooks the ostensible openness of academic publishing to co-produced and public involvement endeavours. We’re all supposed to be embracing that ethos…aren’t we? There is work to do, it seems, in lining up expectations with conventions in co-produced research outputs.

Workshopping involvement at This Sickle Cell Life participatory dissemination event (Photo: Anne Koerber)

Final thoughts

As for the research itself, it’s been a fantastically valuable project for better understanding the health and social conditions of sickle cell, and I’m not just saying that because I helped with it. There are definitely ways we can further improve on our approaches to co-production for next time (though when I see some of the supposedly co-produced work elsewhere in health research, I feel like we’re doing a damn sight better than most!). It’s also not to say that our co-production work was straightforward or easy; on the contrary, it was a very different way of working than what I had been used to, and took a lot of back-and-forth and constant communication between all parties to stay on the same page. But that ongoing relationship, and that time taken to gather views from around the table really ought to be how we always operate: with care, consideration and dialogue between all parties at all times. We came to define it as ‘slow co-production’, which I’ve blogged about before and we lay out what we think are its strengths in this article. It is only within the tight parameters of contemporary academic research contracts that this valuable, lengthy process feels like a luxury or an inefficiency. I should add that the NIHR were very supportive of our approach and helped us build into our budget money to support exactly this kind of process, and they also gave us a generous timeframe in which to generate all this co-produced work.

I also felt humbled by the ethic of care that the project entailed, and it has led to a personal reflexive shift for me as a researcher. Previously, I think I had rather uncritically worked within some of the unhelpful tropes of social science research – including what constitutes ‘knowledge’, who or what entities ‘hold’ knowledge (and you see it performed nowhere more starkly than in healthcare settings), and of the power imbalance between researcher and participant. Now I think twice before internalising the status quo of privilege and position in knowledge-holding (and knowledge exchange). I think more about how practical experience informs knowledge – or is overlooked by systems of knowledge and knowing – and who actually gets a seat at the table in supposedly collaborative endeavours. Cicely and Alicia have written about all of this and more, and you can read this work here, here and here.

Meanwhile, early-career researchers like myself can learn much from the opportunity to do some worthwhile epistemological ‘resetting’ when it comes to thinking about how to plan, frame and conduct our research. Pursuing co-production helps us recognise the importance of prioritising equitable social science research that values all voices equally and recognises a range of expertise, rather than relying on the (often colonial, socially-structured, privileged) expertise bestowed – and often still prioritised – by academia.

Some of the This Sickle Cell Life collaborators (Top row L-R: Patrick Ojeer, Ganesh Sathyamoorthy, Sam Miles, Nordia Willis, Alicia Renedo, Andrea Leigh. Bottom row L-R: Cicely Marston, John James, Siann Millanaise. Photo: Anne Koerber)

This Sickle Cell Life was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (project number 13/54/25). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the HS&DR Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health.

That’s not all: in

That’s not all: in

I thought for a long time about what to write about. My work has been moving over time from

I thought for a long time about what to write about. My work has been moving over time from

Trying to better understand the relationship between sex and sexuality and space is important because beyond theoretical ideas, it has an impact on how a location might influence sexual identity, practices or safety. For example, healthcare interventions for sex workers might depend on a safe space accessible from their working space. Civil rights demonstrations or an

Trying to better understand the relationship between sex and sexuality and space is important because beyond theoretical ideas, it has an impact on how a location might influence sexual identity, practices or safety. For example, healthcare interventions for sex workers might depend on a safe space accessible from their working space. Civil rights demonstrations or an

Beyond MSM populations specifically, this idea of technology redefining community, whether for better or worse (or indeed both!) is crucial to how we understand how technology mediates human behaviour. In a public health context, technology needs to be harnessed in ways which are alert to local conditions, whether that is in terms of unequal access to technology, or an affinity (or restriction) to certain kinds of communication device. At the same time, the widespread adoption of mobile phone technology – 5 billion people

Beyond MSM populations specifically, this idea of technology redefining community, whether for better or worse (or indeed both!) is crucial to how we understand how technology mediates human behaviour. In a public health context, technology needs to be harnessed in ways which are alert to local conditions, whether that is in terms of unequal access to technology, or an affinity (or restriction) to certain kinds of communication device. At the same time, the widespread adoption of mobile phone technology – 5 billion people